NOTE: After re-reading several of Vonnegut’s works, I fell in love with his voice and style all over again. I also gained a new appreciation for the incredible consistency of the themes and ideas put forth from his earliest to latest novels and essays. In January and February of 2016, presidential candidates finally began talking about gun control and gun rights, and I found myself connecting their rhetoric with Vonnegut’s sentiments on the subject.

“And one charmingly suggestive thing I learned (attitude I assumed), was that culture was as separate from the brain as a Model T Ford, and could be tinkered with. It was an easy jump from there to believing, as I do, that a culture can contain fatal poisons which can be identified: respect for firearms, for example, or the belief that no male is really a man until he has had a physical showdown of some kind, or that women can’t possibly understand the really important things which are going, and so on.”

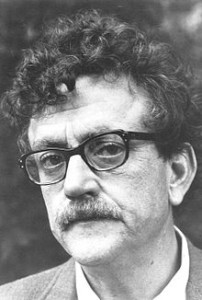

-Kurt Vonnegut Jr., from a letter to Jerome Klinkowitz, 1987. (ed. Wakefield

A Fatal Poison

Most Americans do not live in fear of bobcat attacks or raids from indigenous neighbors. By and large, we’d rather watch birds than hunt them. Violence and intimidation are tragic certainties of daily life for far too many Americans, but guns—for all the technological advancement that has made them deadlier and easier to use—no longer reflect sophistication, but rather a reluctance to free ourselves of an outdated American ethos.

Kurt Vonnegut was a man who knew firearms, and his body of work reflects a harsh judgment of the prevalence of guns and so-called “gun culture” in America. Like Rudy Waltz, the protagonist of his 1982 novel Deadeye Dick, he was raised in a home chockfull of them. Like Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse-Five, he enlisted in the United States Army during World War II, and was present during the allied firebombing of Dresden in 1945 as a prisoner of war. He had been trained from his youth not just to use firearms with accuracy, but to care for them lovingly, maintain them, respect them. Many boys in America’s cities and backwoods alike are still inculcated with the same belief Vonnegut was: firing a gun is a necessary right of passage into manhood.

Robert Heinlein wrote that an armed society is a polite society, while Vonnegut saw an armed society as a terminally ill one. This was a man who knew not only how to fire a gun, but how to disassemble and clean one. A man who many times over had felt the weight of a weapon in his grip, whose finger had fondled countless triggers. He knew enough about guns to know that the civilian belief in their necessity had no place in contemporary America.

The only thing standing in the way of a bad man with a gun is not a good man with a gun. It’s millions of courageous people across this country that are going to pressure law makers into enacting comprehensive gun violence prevention laws, so that bad man won’t be able to get a gun in the first place. It’s not a pipe dream. It’s really possible to make guns that difficult to obtain.

However, it seems that America is moving farther away for such a goal. In 1999, after the tragedy at Columbine, the executive vice president of the NRA made a statement, “We believe in absolutely gun-free, zero-tolerance, totally safe schools. That means no guns in America’s schools, period.” After Newtown, fourteen years later, the same man—Wayne La Pierre—called for armed vigilantes to start patrolling all 100,000 of America’s public schools. As with so many of our nation’s ills, politicians and unelected political operatives alike seem to think that solutions will be forged in public schools, not state and national legislatures.

The bottom line is, comprehensive gun control legislation is effective in decreasing firearm related homicides, suicides, and mass shootings. Brazil, South Africa, and Australia all saw massive and lasting reductions in gun violence after passing comprehensive gun control legislation. The problem here in America is: there isn’t enough political will or courage to tackle the problem head on. Instead, we are left with ineffective, piecemeal legislation (assault weapons ban, concealed carry, voluntary gun buyback) that show mixed results and therefore provide more ammunition for the NRA and other “gun rights” advocates, who are out to prove that laws will not make our schools and movie theaters and houses of worship safer.

Research on the effects of gun control and the prevalence of firearms is also woefully incomplete, as the NRA successfully opposes gun violence prevention research all over the country.

Vonnegut framed his argument against firearms not in legal or technical terms, but in pragmatism. How often does the average American civilian living in a city, suburb, or rural locale require a fast, convenient and impersonal method of disposing of another living thing? If the answer is never, or not very often, then perhaps a firearm is simply no longer the tool for the job. When it comes to the debate on guns, no argument is more out of step with legal precedent, history, or reality, than the invocation of the Second Amendment.

In Its Entirety

Yes, what about the Second Amendment? What about our right to bear arms? Vonnegut meditated on this very question in an essay from his 1991 biographical collage Fates Worse Than Death. I removed the lengthy parenthetical asides to clarify the point:

“I only wish the NRA and its jellyfishy, well-paid supporters in legislatures both State and Federal would be careful to recite the whole of it [the Second Amendment] and then tell us how a heavily armed man, woman, or child, recruited by no official, led by no official, given no goals by any official, motivated or restrained only by his or her personality and perceptions of what is going on, can be considered a member of a well-regulated militia.”

-Fates Worse than Death

It would behoove us to remember that today’s prevailing interpretation of the Second Amendment has not been around forever. The Founding Fathers would cower before the brilliantly efficient and accurate firearms of today. These weapons that, even in the most inexperienced hands, have the power to dole out death wholesale are, according to Vonnegut, “as easy to operate as cigarette lighters.” Being a lifelong smoker, it is not a stretch to believe that Vonnegut would rank cigarettes far, far below firearms on a list of the most destructive ills of modern society.

How many times has the phrase, “guns don’t kill people, people kill people” been uttered at dinner tables and on television screens across the country? Vonnegut would agree wholeheartedly with such a sentiment, tired as it is. He made it a point in a 1982 interview with Larry Miller to mention that every character in each one of his novels is guilty. We all know that guns are not sentient. We all know they can do no harm without a human at the other end. In Deadeye Dick, George Metzger opines on this sentiment following his wife’s death due to the discharge of a rifle from ten blocks away:

“My wife has been killed by a machine which should never have come into the hands of any human being. It is called a firearm. It makes the blackest of all human wishes come true at once, at a distance: that something die.”

-from Deadeye Dick

To borrow another tired aphorism, the devil is in the details. A gun may not have the will to commit a crime, but it grants its handler an entirely inhuman capability: to dispatch death efficiently while sparing the operator the need to get his hands dirty. Making it harder for angry, violent, or ill people to get guns will not abolish the will to do harm, it will put up a very real roadblock between them and their potential victims.

Under mild scrutiny—even under the subjective lens of fiction—the “guns don’t kill people” argument may serve as a conveniently dismissive answer to the gun question, but it offers no solution. There will never be a society free from ill will, and there will always be people who get it in their heads to kill someone. Therefore, firearms are just a scapegoat, right? Not according to Vonnegut. As a former soldier who grew up surrounded by weapons of death, he had learned that a man possessing the will to do harm becomes exponentially more dangerous when he gets his hands on a gun. The fact that there are enough guns in this country to arm every man woman and child to the teeth several times over, only creates a more urgent need for a solution.

Weapons of Mass Chaos

Inextricably linked with Vonnegut’s derision for what we today call “gun culture”, is his professed belief in the awesome power of stories to tweak culture in potentially massive ways. One of Vonnegut’s students, Loree Rackstraw, pointed out her mentor’s preoccupation with this belief in her 1982 review of Deadeye Dick. She writes that Vonnegut knew the dangers of storytelling. He knew that the narratives we Americans gravitate towards are not ones in which the protagonist seeks a quiet, unremarkable end. We would much rather go down in a blaze of glory while seeking revenge for some slight against our honor. One of the many dangers of stories like these is that the protagonist is often pitted against someone who looks different, sounds different, and believes in different things. These stories tell us that our way of life is superior. These stories show impressionable little boys and little girls what they have to do to become adults. For too many little children, that right of passage is obtaining the key to the proverbial gun room.

Vonnegut’s fictional universe is, like our own, chaotic. His characters—Billy Pilgrim and Rudy Waltz, for example—are imbued with the knowledge of this chaos, and so they seem resigned to accept whatever punishment is in store for them, deserved or not. Yet Vonnegut preaches nothing if not love and kindness towards all living things (if the universe turns you into a lemon…) In the context of a chaotic universe, loving and helping others may be the only way to get by.

Firearms represent an antithetical alternative to this gentle acceptance of the universe as chaos. No matter how sophisticated the technology, how perfectly-calibrated the mechanism, how deadly the ammunition, firearms are a feeble defense. They do not make a home safer, they do not cure a man of his discontent, and they do not intimidate hatred or dispel the will to do harm. They are agents of the very chaos and insecurity that they are supposedly meant to protect against.

This is a country where the CDC is not allowed to ask questions about firearms in national surveys to provide a foundation for meaningful research. The country where a gun “rights” activist is shot in the back by her toddler son. Where a five year old shoots and kills his infant brother. Where a three year old discharges daddy’s pistol into his own chest.

Where do the majority of these incidents take place? Not a battlefield, or a street corner. In the home. The supposedly safest, most secure place in the universe. How’s that for chaos?

Stories lie to us. They convince us that we can bring order to a world of chaos by fitting into a particular role. We are comforted by firearms because they provide, among other things, the illusions of safety and control. Instead of trying to fool ourselves into thinking we can bring order to the chaos, Vonnegut would say that we must adapt to it. Disarming ourselves—mastering the illusion of control—is one way to adapt.

It is time for all concerned Americans to start tinkering with our culture. It is time to move past the false narrative of the NRA. Sportsmanship and self-reliance can exist without firearms. Healthy masculinity and personal strength are achievable without firearms. It is time to leach out the toxin that has been poisoning us for over a century:

“While playing with what was supposed to be a toy pistol, which she found in her home, the little daughter of Mrs. Mary James, of Homsteadville, on the outskirts of Camden, yesterday accidentally shot her mother, the bullet striking her in the head.”

-The Times, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 22 February, 1897

Hopefully, the democratic process hasn’t yet been fully coopted by those with a vested interest in perpetuating America’s poisonous culture of firearms. We have the right to stand up, and let our government and our neighbors know where we stand. Change can happen peacefully, even when staring down the barrel of a gun.

Sources/Further Reading:

Alcorn, Ted. “There’s a Pattern in Children Shooting Each Other.” 9 March 2016. Online

Dickinson, Tim. “The NRA vs. America.” Rolling Stone 31 January 2013. Online.

Ingraham, Christopher. “Gun Control: What works, What doesn’t and What’s

Up for Debate.” The Washington Post. 7 March 2016. Online

Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher. “Deadeye Dick by Kurt Vonnegut.” The New York

Times [New York, NY] 5 November 1982. Web.

Manseau, Peter. “When Kids Shoot Their Parents: An American Tradition.” 10 March, 2016 The Trace. http://www.thetrace.org/2016/03/jamie-gilt-accidental-shooting-history.

Marvin, Thomas, ed. Kurt Vonnegut: A Critical Companion. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 2002. Print.

Merrill, Robert, ed. Critical Essays on Kurt Vonnegut. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co. 1990. Print

Offit, Sidney, ed. Kurt Vonnegut: Novels 1976-1985. New York: Literary Classics of the United States: 2014. Print

Vonnegut, Kurt. Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage of the 1980’s. New York. G.P. Putnam and Sons. 1991. Print

Wakefield, Dan, ed. Kurt Vonnegut: Letters. New York: Delacorte Press. 2012. Print